Chronic Myeloid Leukemia

Overview

What is chronic myeloid leukemia (CML)?

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), also called chronic myelogenous leukemia, is a cancer of the blood and bone marrow that progresses slowly. CML is linked to the Philadelphia chromosome, a specific genetic abnormality (mutation) found in the bone marrow cells of most patients with CML. It may also show up in patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) or acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

Our approach to chronic myeloid leukemia

UCSF is dedicated to delivering the most advanced treatment options for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) with care and compassion. For most patients with early-stage CML, medications called tyrosine kinase inhibitors can effectively control the disease for years and will usually prevent it from progressing to the final phase. Should standard treatments fail, UCSF offers stem cell transplants as well as access to clinical trials, which are studies of promising new therapies.

Awards & recognition

-

Among the top hospitals in the nation

-

Best in California and No. 7 in the nation for cancer care

Causes of chronic myeloid leukemia

Genes in your body control cell growth – some promote it, others slow it down. The instructions for this process live in your chromosomes, which are made of inherited DNA. When cells divide, they copy this DNA, and sometimes mutations – changes in the DNA sequence – happen. These differences can impact how your cells grow, which can lead to cancer.

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) occurs when something causes genetic changes in myeloid cells – a type of white blood cell – in the bone marrow. It's unclear what triggers this process. But 90% of people with CML have a genetic change, called the Philadelphia chromosome, that leads to immature myeloid cells multiplying out of control.

Risk factors for chronic myeloid leukemia

We don’t know why some people get the gene mutation that causes CML. It's not hereditary. Still, a few risk factors may increase your chances of getting CML, including:

- Sex. CML is slightly more common in men.

- Age. More than half of CML cases develop in people who are 65 or older.

- Extreme radiation exposure. In rare cases, patients who have been exposed to high doses of radiation develop CML. This amount is far beyond the level of radiation you receive from things like dental X-rays and mammograms.

Phases of chronic myeloid leukemia

CML has three main phases. The difference between the phases is based mainly on the number of the immature myeloid cells in the blood or bone marrow and whether they've spread to other parts of the body.

- Chronic phase. CML almost always starts in the chronic phase. At this point, it's usually easy to control with treatment, and patients can lead nearly normal lives.

- Accelerated phase. The disease may progress over a few years into the accelerated phase. If this happens, patients may experience high fever, bone pain and painful enlargement of the spleen.

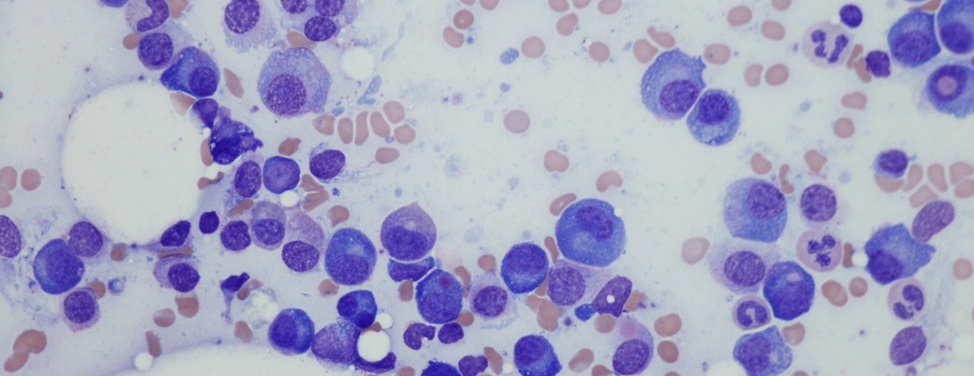

- Blast phase. This final phase of CML is a form of acute leukemia that's difficult to treat. Tests will show that more than 20% of blood or bone marrow samples are immature white blood cells, known as blasts, and that the blasts have spread to tissues and organs beyond the bone marrow. Patients may experience fever, poor appetite and weight loss.

Symptoms of chronic myeloid leukemia

Most patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) initially visit their doctors because they're experiencing:

- Weakness

- Fatigue

- Shortness of breath

- Low-grade fevers

- Night sweats

- Bone pain

- Weight loss without trying

- Pain or a feeling of abdominal fullness

Many of these symptoms occur because the CML cells are crowding out the bone marrow's healthy red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets.

Diagnosis of chronic myeloid leukemia

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is generally suspected when blood tests show an elevation in white blood cells and there's no illness or infection to account for it.

The diagnosis is confirmed through genetic tests that look for either the Philadelphia chromosome or a gene mutation called BCR-ABL. Either can be responsible for making the myeloid cells grow out of control.

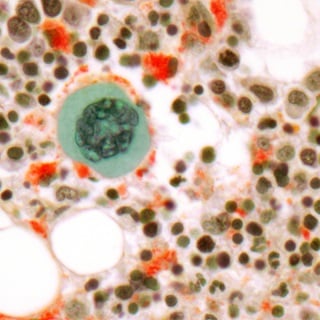

To help determine the stage of the cancer, a bone marrow aspiration (obtaining a sample of fluid) or bone marrow biopsy (obtaining a sample of solid tissue) may be performed so that the leukemia cells can be examined under a microscope.

Treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia

The main treatment for CML is targeted therapy – using drugs or other substances that can identify and attack cancer cells. However, other treatments are available for patients depending on their overall health and the phase of their CML.

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) for CML

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) are drugs used for targeted therapy. They block the protein produced by the BCR-ABL gene that makes white blood cells multiply uncontrollably. These drugs include imatinib (Gleevec), dasatinib (Sprycel) and nilotinib (Tasigna). They're taken orally.

Targeted therapy is effective in 80% of CML patients. In successful cases, the Philadelphia chromosome disappears and normal blood counts are restored. For most patients, TKIs prevent CML from progressing to the accelerated or blast phase.

Patients can survive a long time on TKIs, but whether these drugs actually cure CML is unknown. While taking TKIs, patients are monitored with a blood test every three months and an annual bone marrow aspiration and biopsy.

Stem cell transplantation for CML

Another highly effective option for treating CML is a stem cell or bone marrow transplant (BMT). Typically, the transplant uses stem cells collected from a matched donor, a process called allogeneic transplant. This is a risky procedure, with a treatment-related death rate of 15 to 20%, so it's only for patients who don't respond to TKIs.

Chemotherapy for CML

Chemotherapy used to be a common treatment for CML. However, TKIs are now known to be more effective, so chemotherapy will be used only if TKIs aren't working or as part of a stem cell transplant.

Radiation therapy for CML

Radiation is used only under certain circumstances. For example, it may be used to shrink an enlarged spleen that's causing symptoms, such as loss of appetite. Radiation may also be administered as part of a stem cell transplant or to treat bone pain caused by leukemia cell growth in the bone marrow.

Investigational therapies for CML

UCSF is dedicated to improving outcomes for patients with CML. Interested patients may have opportunities to participate in clinical trials investigating promising treatments for chronic myeloid leukemia.

UCSF Health medical specialists have reviewed this information. It is for educational purposes only and is not intended to replace the advice of your doctor or other health care provider. We encourage you to discuss any questions or concerns you may have with your provider.

Where to get care (1)

Recommended reading

Related clinics (4)

Osher Center for Integrative Health

2

2